Introduction

Energy for muscles

Types of muscles

Introduction

How do muscles contract? Glad you should ask. Look in any book and you’ll probably be scarred and put off completely. I know I was! I mean what is the deal with Z line, A band, I band…?!

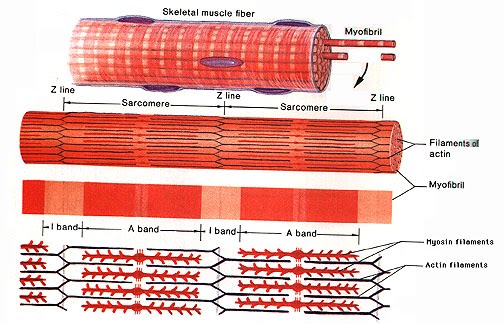

So let’s look into it very gently indeed. First off, a good idea about what muscles look like on a bigger scale:

The muscle is attached to the bone (spot the nice bone marrow) by the tendon. Muscle cells have a plasma membrane and cytoplasm much like any other cell, but each has a special name. The membrane is called sarcolemma while the cytoplasm is called sarcoplasm (it has a much higher glycogen storage content).

The basic unit of muscle tissue is the myofibril which has a tube-like shape and is made up of the muscle cells themselves. These look fibrous and are organised into myoflilaments.

The bread and butter of muscle cells (more bread -11% protein- and less butter!-1% protein) are 2 types of protein that work together to cause contraction. Because muscle contracts, never “extends”. That’s why our arms and legs have muscles on opposing sides, so that that contraction of each may result in either a “push” motion or a “pull” motion.

On a smaller scale, myofibrils contract as a result of those 2 proteins sliding along one another. Those 2 proteins damn right deserve a name, so let’s call them actin and myosin just because that’s what everyone else who speaks English and has any awareness whatsoever of them calls them. Actin appears lighter under a microscope than myosin, so a lovely colour pattern can be observed.